- Home

- Media Relations

- Out of Step: What’s Going On within Beijing’s Top Party Leadership?

GIGA Insights | 15/04/2024

Out of Step: What’s Going On within Beijing’s Top Party Leadership?

Beijing’s charm offensive

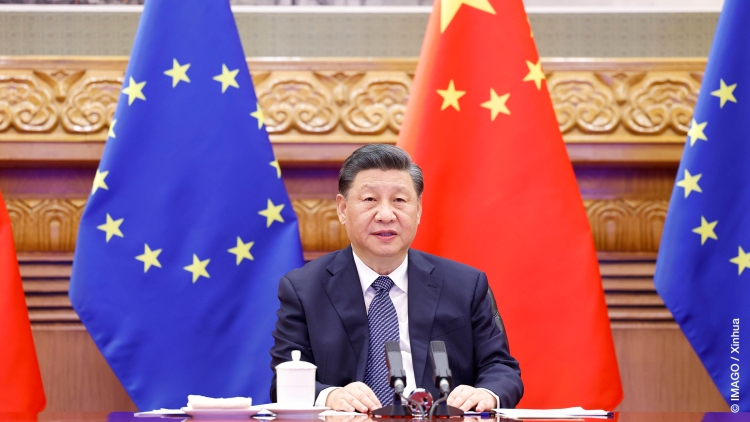

These days in Beijing, there is a revolving door of representatives from foreign governments. Following visits by high-ranking envoys from the United States, Japan, and the Philippines, German chancellor Olaf Scholz will meet with China’s party-state leadership today, followed by French president Emmanuel Macron in May. Via this carefully staged charm offensive, Beijing is trying to counteract the trend of de-risking and diversification. The Chinese leadership is reacting to foreign investments in its neighbourhood with the slogan “The next China is still China,” a self-confident play on the idea that “up-and-coming” countries such as India, Vietnam, and Indonesia are each being spoken of as “the next China.”

Issues at the top of Western agendas, however, surround how to achieve fair market access given lower dependency on the Chinese economy, along with a desire for clarity on China’s relationship to Russia. All in all, this difficult situation demands that the Europeans perform a diplomatic tightrope act on topics of economic cooperation, technological competition, and (geo)political rivalries.

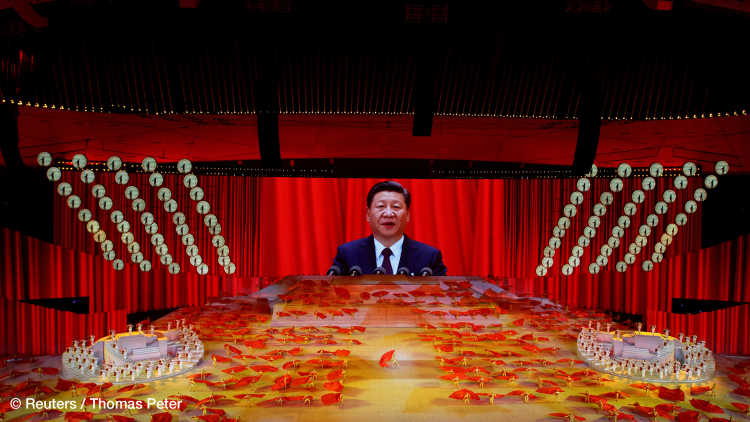

In the course of these discussions, however, it is routinely overlooked that the central leadership of the Chinese Communist Party – where the power centre is located – is currently in a peculiar state of limbo: Whoever shakes President Xi Jinping’s hand would do best to remember they are simultaneously paying homage to him as the general secretary of the CCP and as the country’s top military leader. However, the party itself, from whose leadership Xi’s unparalleled authority draws, has been out of step for the past half year. This situation begs the question of how capable of decision-making and how united Zhongnanhai is regarding economic, security, and geopolitical strategies.

Intentional signals of continuity from the government …

The Chinese government gives off an air of normalcy and continuity. There was virtually nothing new in terms of content in Prime Minister Li Qiang’s report at the session of the National People’s Congress that took place in March of this year: economic goals and budget numbers met expectations, existing trends are to be continued with the rhetorical invocation of digital and technological innovations in the form of “new quality productive forces.” Demonstrative of this are formulations regarding reunification with Taiwan, assimilation of ethnic minorities, and “an equitable and orderly multipolarisation of the world.”

There was disappointment among those who, in advance of the session, had hoped that important personnel decisions would be taken. Especially poignant was that no regular successor was named for Qin Gang, the foreign minister who was removed from his position in summer 2023 following accusations of spying. Instead, former foreign minister Wang Yi will continue to substitute. Wang was promoted to head the CCP’s Central Foreign Affairs Commission in fall 2022, giving him the last word in foreign affairs anyway.

… and unintentional signals from the party’s highest echelons

There is, however, no sign of normalcy or continuity emanating from the top party leadership. On the contrary, institutional routines and certainties have long since been abrogated, with paralysing consequences for the state apparatus as a whole. The Third Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the CCP was supposed to take place in the fall of 2023. This approximately 200-person committee had held to a regular session schedule since the 1990s, with the exception of 2018. According to this schedule, the Third Plenary Session in 2023, planned to convene a year after the Twentieth Party Congress of October 2022, was supposed to lay the personal and political groundwork for Xi Jinping’s third term in office. Instead, this important plenary session was indefinitely delayed, with unforeseeable consequences for the Chinese government’s ability to act and take decisions at all administrative levels.

This interruption of institutional routines at the Central Committee serves to explain not just why there has been a lack of new political areas of emphasis despite economic imbalances and geopolitical challenges, but also why the prime minister’s press conference, which has traditionally been fixed to the end of the annual sessions of the National People’s Congress, was suddenly scrapped this March. Li Qiang’s fielding of questions from domestic and foreign journalists is not envisaged for the coming years either, given the risk of statements being made without prior approval.

Party leadership: Paralysed, or excessively powerful?

The continuing silence in the forest of Zhongnanhai can be interpreted in many different ways. The simplest explanation, though certainly not the only one, is that Xi Jinping is purposely lingering in the background so long as the economic situation continues to be difficult, in an attempt to fob off responsibility onto his prime minister. A similar situation occurred in 2020, when Xi handed over the reins to Vice Prime Minister Sun Chunlan in the fight against COVID-19; Sun orchestrated the first lockdown in Wuhan, among other things. Only when the first wave of infections had waned did Xi return to the political limelight as a hero in the fight against the virus.

Another interpretation, often proffered by foreign analysts of China, is that a power struggle is occurring off-stage. It is posited that a bitter conflict is raging in the party’s highest echelons between supporters and opponents of Xi Jinping. According to this interpretation, Xi is under pressure from a series of party veterans who hold him responsible for the current economic problems, above all in the real estate, finance, and tech sector. This sustained conflict among the power elite is resulting in paralysis at the top leadership levels and a general loss of political orientation.

It is conceivable, however, that a third, contrary interpretation holds water – namely, that Xi Jinping’s authority has become so consolidated and uncontestable that he can simply override prevailing institutional rules and routines. As chair of numerous central party commissions with inter-agency leadership competency – e.g. the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform, the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, and the National Security Commission – Xi is at the helm of his country’s destiny. He may have the clout to sidestep the lengthy and complex consultation process that usually precedes the plenary sessions of the CCP’s Central Committee.

How to evaluate these various signals remains unclear. Regardless of whether Xi Jinping is facing pressure at home or is, in fact, able to act autonomously, the deferral of the Third Plenary Session is not a good sign for consensus-building among the political elite. Even if the official charm offensive seeks to convey a sense of stability and continuity, there are doubts about the clarity and coherence of the political thrust of the party leadership. Foreign actors will likely remain in the dark about China’s future direction for a while, as will most of their Chinese counterparts.

Experts

Text: York Frerks, Heike Holbig

Translation: Meenakshi Preisser